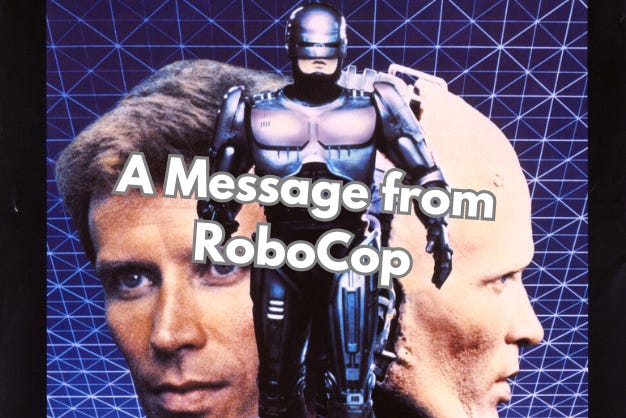

Technology Fixes and Robocop

Technological fixes aren't the only fixes, even if robots are pretty cool

The 1987 film RoboCop is not the movie I expected. I expected a typical action movie, the kind where the plot is in service to the action. I love these kinds of films and expected RoboCop to conform to the genre. However, I got an anti-corporate critique that showed me the underlying mechanisms that drive technological solutions.

I was born after RoboCop’s debut in the late 80s. I only knew of the world that RoboCop was responding to through vague references to Detroit being a place to avoid, and how crime was at the time. It felt more like a bygone time that people were responding to rather than something relatively recent, something that still impacts the black community and the region to this day. RoboCop responds to the issues of crime in America and critiques the solutionist perspective that captures our everyday sentiment.

Lyseology

I’m glad I watched RoboCop near the same time I read Robert Braun’s paper “Radical Reflexivity, Experimental Ontology, and RRI”. Without it, I would not have as precise of a term to explain what RoboCop is critiquing, and so I treat it as a great fortune that the paper was published just a week or two before I watched RoboCop. RoboCop is a film that critiques the way technology corporations, and by extension, the larger science enterprise convinces “policymakers and the general public that the present possesses some form of lack that should be addressed with a new technology brought to life and offered as a solution”. I pulled this quote directly from Braun’s article in his creation of the word Lyseology (pronounced Lee-See-ology). In other words, lyseology refers to how the larger science and technology enterprise convinces us that the only way to solve problems is through a technological fix, and through that convincing becomes the only way we can see, blinding us to all other ways of seeing the world.

RoboCop critiques our lyseologic perspective not through grandstanding moral narratives, but through satire far more subtle than I’m used to.

RoboCop

The Omni Consumer Products (OCP) building towers in Detroit. The CEO of OCP discusses his vision of building Detroit anew into Delta City and sees privatization as the path forward to accomplish this. A privatized police force, to address the rampant crime, is the path ahead to achieve this.

This situation is exactly the lyseologic view, where corporate entities see a lack—the poor crime response in Detroit—and seek to address it with a technological fix. The logic that introduces robots into police departments, because the rate of crime outpaced the ability of the policy to respond, makes sense. This common-sense feeling shows how significant lyseology as a worldview has seeped into our being.

Alex Murphy is killed on the job, and based on the contract of the Detroit Police Department, Alex Murphy is pulled into OCP’s RoboCop program where he becomes the first Robocop. In becoming RoboCop, Murphy is stripped of his memories and all his human parts except the lower part of his face (for some reason). We get this fun super cop montage of how effective RoboCop is in responding to crime, and so we see that the product works. OCP has achieved the 24/7 cop.

Contrary Point: Abbott, the graphic novel

The graphic novel Abbot is about the same era of Detroit. The difference between Abbott’s response to crime versus what RoboCop shows can help you understand what other ways of looking at things might mean. The novel Abbott addresses the problem of crime through revelation. The way to solve crime is through the illumination of facts which will then lead to better outcomes. No technological introduction—Abbott isn’t a sci-fi, it’s a fantasy true crime—but instead the ideals of truth and understanding. Where RoboCop says there is a gap to fill with technology, Abbott says people must understand what is happening.

Imagining the otherwise becomes possible first by understanding the lenses we’ve adopted. Lyseology instructs us on our dominant lens that forces us to see a lack that has to be filled by a new fancy gadget.

Final Thoughts

Lyseology can readily promote the “technology can only be bad” narrative. This is not what I want to critique, nor is it Dr. Braun’s. The default world view which makes technological solutions the only sensible solution to a given problem is the culprit here. Dr. Braun wants people, through the lens of lyseology, to imagine other-than-technological solutions. At the core of RoboCop, for all its subtle satire, is the same message. The being fixed to technological solutions is our default stance, this is how we get a privatized police force making 24/7 surveillance robots instead of reducing crime. RoboCop is a call to not imagine the world it has created, but away from it.